The Oldest Cemeteries in the World: A Journey Through Time

Cemeteries are not simply resting places for the dead; they are living archives of human history, silent storytellers whispering across centuries. Each grave marker, burial mound, or sacred cave is a cultural artifact, embodying the values, fears, and beliefs of those who once walked the earth. If you’ve ever wondered where the very first cemeteries were, buckle up—we’re about to embark on a journey through time, tracing humanity’s oldest sites of remembrance.

Contents

- What Makes a Cemetery a Cemetery?

- The Oldest Cemeteries in the World

- 1. Qafzeh Cave, Israel (c. 100,000 years ago)

- 2. Sungir, Russia (c. 34,000 years ago)

- 3. Dolmen Sites, Europe (c. 4000–3000 BCE)

- 4. Uan Muhuggiag, Libya (c. 5000 BCE)

- 5. Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria (c. 4600–4200 BCE)

- 6. Ur Cemetery, Mesopotamia (c. 2600 BCE)

- 7. Kerameikos Cemetery, Greece (c. 1200 BCE onward)

- 8. Mount of Olives, Jerusalem (c. 3,000 years ago to present)

- Why Do Ancient Cemeteries Matter Today?

- Modern Lessons from Ancient Graves

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

What Makes a Cemetery a Cemetery?

Before we start, let’s get one thing straight: defining the “oldest” cemetery isn’t as simple as pointing to a patch of land with a few skeletons. Archaeologists distinguish between isolated burials and organised cemeteries.

A single grave can be evidence of ritual, but a cemetery is a collective—an intentional, shared space dedicated to the dead. Think of it as the difference between a lone diary entry and an entire library.

A cemetery implies something more deliberate than a handful of burials scattered across millennia. It’s a communal space, designed and used repeatedly by a group for the purpose of interment.

To put it simply, a single grave is personal; a cemetery is cultural. One is a whisper, the other a chorus.

So what makes a cemetery? Scholars often look for three key features:

- Multiple Burials in One Place – Evidence that a site was revisited over time, showing intentionality rather than coincidence.

- Ritual and Symbolism – Signs of burial practices beyond the practical, like grave goods, ochre staining, or carefully positioned bodies. These indicate belief systems and collective memory at play.

- Designated Space – A defined area set apart for the dead, whether through markers, boundaries, or monumental structures.

It’s also important to note that cemeteries reflect social organisation. The moment a community starts dedicating space to its dead, it acknowledges shared identity, continuity, and even hierarchy. In many ways, the first cemeteries were humanity’s earliest attempts at urban planning—organising not for the living, but for the dead.

This distinction matters because it elevates cemeteries beyond the biological reality of death into the cultural sphere of meaning, remembrance, and ritual.

The Oldest Cemeteries in the World

1. Qafzeh Cave, Israel (c. 100,000 years ago)

Welcome to one of the oldest known burial grounds in human history. Discovered in the Galilee region, the Qafzeh Cave holds remains of Homo sapiens dated to around 100,000 years ago. Here, bodies were buried with ochre (a natural pigment) and grave goods like deer antlers.

Why does this matter? Because it reveals that even early humans had concepts of ritual, symbolism, and perhaps even an afterlife. Imagine that: tens of thousands of years ago, our ancestors were already trying to make sense of death with the tools of meaning-making we still use today.

2. Sungir, Russia (c. 34,000 years ago)

Fast-forward to Ice Age Europe. The Upper Paleolithic site of Sungir near Vladimir, Russia, is home to extraordinary burials of a man and two children. These weren’t simple graves—they were treasure troves. The bodies were adorned with thousands of ivory beads, spears, and jewellery.

What’s striking is the labour involved: crafting tens of thousands of beads meant hundreds of hours of work. In other words, the living poured time and energy into honouring the dead. It was both art and ritual, a statement of social status and spiritual belief.

3. Dolmen Sites, Europe (c. 4000–3000 BCE)

If you’ve ever seen a massive stone table-like structure in the middle of a field, chances are you’ve stumbled across a dolmen. Found across Europe—from Ireland to Spain to Korea—these megalithic tombs served as collective burial chambers.

Dolmens weren’t just graves; they were engineering marvels. Imagine hauling multi-ton stones without cranes or bulldozers. These sites reveal communities working together, united by respect for the dead and perhaps awe of cosmic forces. In fact, many dolmens align with celestial events—an ancient link between the eternal sky and mortal remains.

4. Uan Muhuggiag, Libya (c. 5000 BCE)

In the Sahara desert lies a cemetery that challenges stereotypes of the ancient world. Uan Muhuggiag revealed a child mummy dated to around 5000 BCE—long before Egyptian mummification practices. This suggests that North Africa had its own funerary innovations.

It’s a reminder that the story of death isn’t written by one civilisation alone. From the desert sands of Libya to the Nile, burial traditions were diverse, experimental, and deeply cultural.

5. Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria (c. 4600–4200 BCE)

Gold glitters even in the grave. The Varna Necropolis, discovered on the Black Sea coast, is one of the most significant prehistoric cemeteries in Europe. Burials here contained the oldest known gold artifacts in the world—intricate jewellery and ceremonial objects.

Varna tells us that wealth inequality is nothing new. Some graves overflowed with treasures, while others were nearly empty. The dead, it seems, reflected the hierarchies of the living.

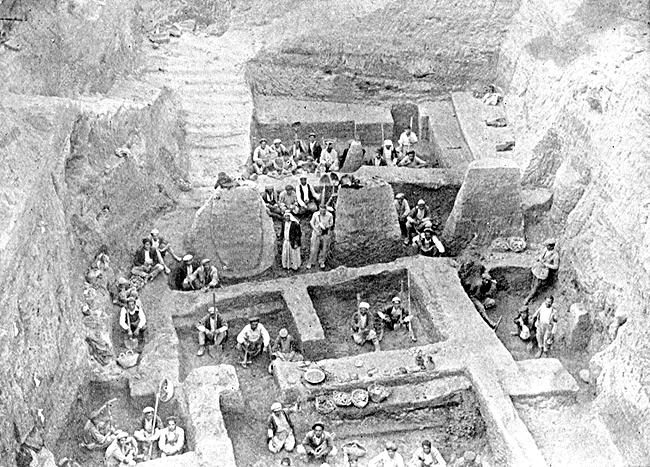

6. Ur Cemetery, Mesopotamia (c. 2600 BCE)

If ancient cemeteries had red carpets, the Royal Cemetery of Ur in modern Iraq would be the Oscars. Excavated by Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1920s, it revealed lavish burials of Mesopotamian elites, complete with chariots, jewellery, and even human sacrifices.

Ur illustrates a sobering truth: for some, the afterlife was a continuation of earthly privilege. The royals took servants and possessions with them—whether the servants liked it or not. It’s both fascinating and chilling, showing how power extended beyond the grave.

7. Kerameikos Cemetery, Greece (c. 1200 BCE onward)

If Athens was the cradle of democracy, Kerameikos was the cradle of Athenian death culture. Used for over a thousand years, this cemetery became the final resting place for soldiers, politicians, and ordinary citizens. Its carved stelae (grave markers) are masterpieces of classical art.

Walking through Kerameikos today feels like flipping through a visual diary of ancient Greece. The imagery—farewells between family, warriors departing for war—captures both the personal and the political dimensions of death.

8. Mount of Olives, Jerusalem (c. 3,000 years ago to present)

Still in use today, the Mount of Olives is one of the world’s oldest continuously active cemeteries. According to Jewish tradition, those buried here will be the first to rise during the resurrection of the dead.

With its panoramic view of the Old City, the site is a reminder of how death is inseparable from landscape, religion, and identity. The Mount of Olives is not just a burial ground—it’s a theological stage.

Why Do Ancient Cemeteries Matter Today?

You may be wondering: what’s the point of digging up old bones? Isn’t death universal? Yes—but how we handle it tells us everything about how societies understand life.

Ancient cemeteries are time capsules. They reveal social hierarchies, artistic achievements, religious beliefs, and even trade networks. They are museums without walls, teaching us that death has always been more than the end; it is an act of cultural expression.

Modern Lessons from Ancient Graves

From Qafzeh Cave to the Mount of Olives, the oldest cemeteries remind us that remembrance is a human constant. The materials change—ivory beads give way to marble headstones, ochre to polished bronze—but the impulse remains the same.

To bury is to care. To commemorate is to connect. And to build cemeteries is to admit that while we may not conquer death, we can shape its narrative.

Bottom Line

The world’s oldest cemeteries are not just dusty archaeological sites; they are mirrors reflecting humanity’s evolving dance with mortality. From ochre-stained bones to golden tombs, these ancient grounds remind us that to honor the dead is also to affirm life. Next time you stroll through a cemetery—whether modern or ancient—remember that you are walking through a story thousands of years in the making.

FAQs

The Qafzeh Cave in Israel, dating back about 100,000 years, is one of the earliest known burial sites for Homo sapiens.

Grave goods reflected beliefs in an afterlife, social status, or served as offerings to gods or ancestors.

Yes, many sites like Kerameikos in Greece or the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem remain open to visitors and pilgrims.

Through excavation, carbon dating, DNA analysis, and study of artifacts to understand cultural and historical contexts.

They remind us that remembrance is a universal act—linking us across time, culture, and geography.

Leave a Reply