Why Do People Visit Graveyards? The Psychology of Dark Tourism

Graveyards. For some, they’re places of sorrow; for others, a tranquil garden of remembrance. Yet for a growing number of travellers, cemeteries are destinations—sites of fascination, beauty, and even inspiration. From the iconic Père Lachaise in Paris to the hauntingly ornate Recoleta in Buenos Aires, graveyards have become magnets for the curious. But why? What drives people to stroll among the dead while on holiday?

Welcome to the strange, compelling world of dark tourism—the act of visiting places associated with death, tragedy, and the macabre. Graveyards, it seems, sit at the heart of this peculiar yet deeply human impulse.

Contents

- What Exactly Is Dark Tourism?

- The Psychological Pull: Confronting Mortality Without Fear

- Cemeteries as Museums of Memory

- The Aesthetic Appeal: Beauty in Decay

- Spiritual Curiosity and the Search for Meaning

- The Allure of the Famous Dead

- Cemeteries as Social Commentary

- Dark Tourism vs. Respect: The Ethics of Visiting Cemeteries

- Why Graveyards Still Matter in the 21st Century

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

What Exactly Is Dark Tourism?

Before we start unearthing the psychology, let’s clarify what we mean by dark tourism. Coined in the 1990s by researchers Lennon and Foley, the term refers to travel to sites associated with death, disaster, or suffering—think battlefields, concentration camps, and, yes, cemeteries.

Unlike mainstream tourism, which celebrates joy, dark tourism invites reflection. It’s about connecting with mortality, history, and meaning. A cemetery visit is rarely just a morbid curiosity—it’s often an attempt to make sense of death and, by extension, life itself.

The Psychological Pull: Confronting Mortality Without Fear

So why do people willingly enter places that remind them of death? The answer lies in psychology.

Humans, as it turns out, are paradoxical creatures. We fear death, yet we’re drawn to it. This tension is at the core of what psychologists call Terror Management Theory (TMT)—the idea that awareness of mortality motivates us to find purpose and permanence.

When we visit cemeteries, we’re engaging with our fear in a controlled way. We walk among gravestones not to flirt with morbidity, but to reaffirm life’s meaning. Graveyards, in this sense, are not morbid—they’re existential mirrors.

It’s a bit like peering into the abyss and realising it’s not as terrifying as we thought.

Cemeteries as Museums of Memory

Let’s set aside psychology for a moment and consider cemeteries as cultural spaces. Each epitaph, statue, and mausoleum tells a story. These stories—etched in stone—transform cemeteries into open-air museums of memory.

Every graveyard reflects the society that built it. The grand marble angels of the Victorian era reveal a culture obsessed with virtue and mourning; the minimalist headstones of modern cemeteries echo our streamlined relationship with death.

Visiting these spaces allows us to read history through its silences. We learn how people of the past understood love, faith, grief, and the afterlife. Graveyards are not only about the dead—they are about the living memory of humanity.

The Aesthetic Appeal: Beauty in Decay

Let’s be honest—many people visit graveyards simply because they are beautiful.

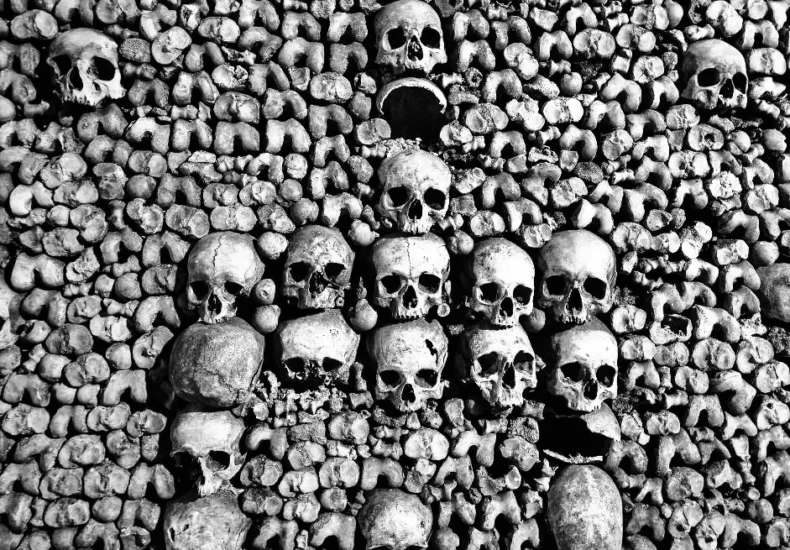

Think of the ivy-clad gothic sculptures of London’s Highgate Cemetery or the marble labyrinths of Genoa’s Staglieno. Cemeteries are often masterpieces of landscape architecture and funerary art. They combine nature, sculpture, and architecture in ways that blur the line between melancholy and magnificence.

In these spaces, decay becomes aesthetic. Time paints its own patina on stone; moss becomes an artist. For photographers, artists, and poets, cemeteries offer what few places can: a tangible expression of impermanence and beauty intertwined.

It’s not morbid curiosity—it’s an appreciation for the art of remembrance.

Spiritual Curiosity and the Search for Meaning

Another powerful reason people visit cemeteries is spiritual, not touristic. You don’t have to be religious to feel something profound in a cemetery. The hush, the symmetry, the whisper of the wind through cypress trees—all evoke a meditative state.

Cemeteries are among the few remaining spaces where modern humans can contemplate mortality without distraction. They remind us of our smallness in the cosmic order and, paradoxically, of our importance in it.

For some, visiting graves is a form of pilgrimage—whether to the tomb of a saint, a celebrity, or a beloved ancestor. For others, it’s a quest for continuity, a connection with generations past. In an age of digital immortality, these encounters with physical mortality feel grounding.

The Allure of the Famous Dead

Let’s not ignore another truth: people love celebrity even in death.

Pilgrims flock to Jim Morrison’s grave at Père Lachaise, leave lipstick marks on Oscar Wilde’s tomb, and scatter flowers over Eva Perón’s resting place. These acts are not only homage but also a form of communion—the desire to be near greatness, even if it’s long gone.

Visiting the graves of famous figures offers a way to bridge time and identity. It’s the tangible proof that legends were once flesh and bone, as mortal as the rest of us.

Cemeteries as Social Commentary

Cemeteries also serve as sociological texts, quietly recording inequality, ideology, and cultural change.

The contrast between elaborate mausoleums and modest graves tells stories of class and privilege. The presence (or absence) of women, children, or marginalised groups in certain burial grounds exposes social hierarchies that persist even in death.

To walk through a cemetery is to walk through history’s unwritten margins. In this sense, graveyards are both archives and arguments—they preserve, but they also provoke.

Dark Tourism vs. Respect: The Ethics of Visiting Cemeteries

Of course, not everyone is comfortable with the idea of visiting cemeteries for leisure. Critics argue that dark tourism risks turning mourning into spectacle. And they have a point.

There’s a fine line between education and exploitation. Responsible dark tourism is about respectful engagement, not voyeurism. It means recognising that cemeteries are sacred to someone, even if they are now heritage sites.

Taking selfies beside tombstones might be poor taste—but walking thoughtfully among them, learning their stories, and preserving their history? That’s cultural stewardship.

Why Graveyards Still Matter in the 21st Century

In a world obsessed with speed, youth, and consumption, cemeteries offer something radical: stillness. They are the antidote to digital overstimulation and instant gratification.

To visit a graveyard is to press pause on life’s noise and listen to the silence of time. It’s not escapism—it’s remembrance, reflection, and renewal.

Graveyards remind us that life’s value is measured not by its duration but by its depth.

Bottom Line

So, why do people visit graveyards? Because they are mirrors. They reflect who we were, who we are, and who we will one day become.

Cemeteries aren’t places of death—they’re repositories of life’s meaning. Within their quiet boundaries lie not only the remains of the past but also the whispers of humanity’s eternal questions.

Dark tourism, then, isn’t about morbidity. It’s about understanding ourselves through the presence of death.

After all, in the company of the dead, we remember how to live.

FAQs

Dark tourism is the act of visiting places linked to death, tragedy, or suffering—such as cemeteries, battlefields, or memorials—to learn, reflect, or pay respect.

Not if done respectfully. Avoid loud behaviour, don’t touch graves unnecessarily, and be mindful that these are sacred spaces for many people.

Notable examples include Père Lachaise (Paris), Recoleta (Buenos Aires), Highgate (London), and Arlington National Cemetery (Washington D.C.).

Cemeteries preserve art, architecture, and the social history of the time. They reflect cultural attitudes toward death, class, and identity.

Research the site’s history before visiting, behave respectfully, avoid intrusive photography, and support local preservation efforts.

Leave a Reply