Buried in Style: The Most Extravagant Tombs in History

Death, inconvenient as it may be, has never stopped humans from showing off. If anything, it has encouraged us to do so permanently. Across civilisations, tombs have functioned as more than resting places for the dead; they are architectural manifestos, political statements, and unapologetic displays of wealth, power, and ego. Why settle for eternal rest when you can have eternal admiration?

From pyramids visible from space to mausoleums that resemble small palaces, the most extravagant tombs tell us far more about the living than the dead. They reveal what societies valued, feared, worshipped, and desperately wanted to be remembered for. So let’s take a walk—respectfully, of course—through history’s most lavish final addresses and ask the obvious question: what were they trying to prove?

Contents

- Why Humans Build Extravagant Tombs

- The Great Pyramid of Giza: The Original Power Move

- The Taj Mahal: Grief, Love, and White Marble Excess

- Mausoleum at Halicarnassus: The Tomb That Named Them All

- Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum: An Army for the Afterlife

- The Medici Chapels: Banking Wealth Meets Divine Aesthetics

- Napoleon’s Tomb: Imperial Minimalism (With a Twist)

- Modern Extravagance: Mausoleums of the 20th Century

- What Extravagant Tombs Reveal About Us

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

Why Humans Build Extravagant Tombs

Before we get to the marble, gold, and architectural excess, it’s worth asking why extravagance follows us into the grave. Tombs serve three enduring purposes:

- Immortality through memory: If the body decays, the monument remains.

- Status preservation: Death does not erase social hierarchy—it fossilises it.

- Spiritual insurance: Many cultures believed grandeur pleased gods or ensured safe passage to the afterlife.

Think of tombs as ancient LinkedIn profiles—curated legacies carved in stone. And some profiles were… aggressively optimised.

The Great Pyramid of Giza: The Original Power Move

Location: Giza, Egypt

Date: c. 2560 BCE

No list of extravagant tombs can start anywhere else. The Great Pyramid of Giza is not just a tomb; it is the tomb—the architectural equivalent of dropping the mic and walking off the stage of history.

Built for Pharaoh Khufu, this limestone colossus stood as the tallest man-made structure on Earth for nearly 4,000 years. Let that sink in. Modern skyscrapers come and go, but Khufu’s ego remains structurally sound.

The pyramid’s design reflects ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, astronomy, and divine kingship. Its precise alignment with cardinal points suggests cosmic significance, while its sheer scale screams one thing: this man was not planning on being forgotten.

Extravagant? Absolutely. Subtle? Not remotely.

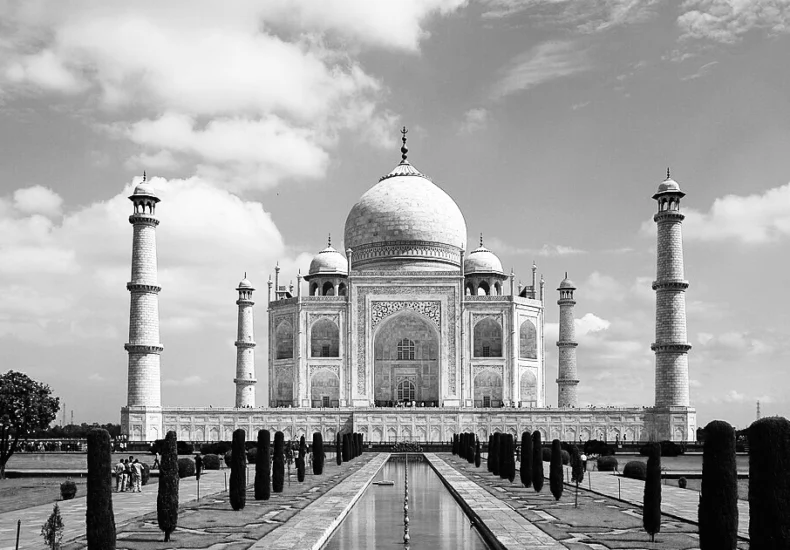

The Taj Mahal: Grief, Love, and White Marble Excess

Location: Agra, India

Date: 1632–1653

If the Great Pyramid is about power, the Taj Mahal is about love—extravagant, obsessive, budget-annihilating love. Commissioned by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, this mausoleum transforms grief into architectural poetry.

Clad in white marble that shifts colour with the sun, the Taj Mahal blends Islamic, Persian, and Indian design into a perfectly symmetrical dreamscape. Precious stones are inlaid with surgical precision, floral motifs symbolise paradise, and calligraphy whispers Quranic verses about eternity.

Was it necessary? No. Was it emotionally excessive? Entirely. And that’s precisely the point. The Taj Mahal proves that mourning, when paired with imperial resources, can result in one of the world’s most iconic structures.

Mausoleum at Halicarnassus: The Tomb That Named Them All

Location: Bodrum, Turkey

Date: c. 350 BCE

The word mausoleum exists because of this tomb. Mausolus, a Persian satrap with excellent branding instincts, ensured his final resting place would define architectural vocabulary forever.

Standing approximately 45 meters tall and adorned with sculptures by the finest Greek artists of the time, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus fused Greek, Egyptian, and Lycian styles into a cultural power cocktail. It was so impressive that it became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Though destroyed by earthquakes, its influence persists. Not bad for a man whose main legacy is, quite literally, being buried well.

Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum: An Army for the Afterlife

Location: Xi’an, China

Date: c. 210 BCE

If you’re going to rule an empire in life, why not take one with you into death? Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor, took this idea very seriously.

His tomb complex includes the famous Terracotta Army—thousands of life-sized soldiers, each with unique facial features, positioned to protect him in the afterlife. This wasn’t symbolic; it was logistical. The emperor expected trouble on the other side.

The mausoleum itself remains largely unexcavated, rumored to contain rivers of mercury and celestial ceilings. Extravagance here isn’t decorative—it’s militarised. Death, apparently, was just another battlefield.

The Medici Chapels: Banking Wealth Meets Divine Aesthetics

Location: Florence, Italy

Date: 16th–17th century

The Medici family didn’t just dominate Renaissance politics and finance—they curated death like an art exhibition. The Medici Chapels are an opulent fusion of marble, sculpture, and religious symbolism, designed to reinforce the family’s divine right to rule.

Michelangelo himself contributed to the New Sacristy, sculpting allegorical figures like Night and Day. Because when you’re a banking dynasty, even your tomb needs original artwork.

These chapels function as a reminder that wealth, when combined with artistic patronage, can secure cultural immortality. Or at least a very impressive tourist attraction.

Napoleon’s Tomb: Imperial Minimalism (With a Twist)

Location: Paris, France

Date: 1840

Napoleon Bonaparte’s tomb at Les Invalides is fascinating because it pretends to be restrained. Encased in red quartzite and positioned beneath a soaring dome, the tomb radiates controlled grandeur.

Visitors must look down upon the sarcophagus—a deliberate design choice reinforcing Napoleon’s dominance even in death. It’s minimalist imperialism: less ornamentation, more psychological architecture.

Extravagance doesn’t always glitter. Sometimes it looms.

Modern Extravagance: Mausoleums of the 20th Century

You might think tomb extravagance faded with ancient empires. You’d be wrong.

- Lenin’s Mausoleum (Russia): A preserved body on public display, because why stop ruling when you’re dead?

- Eva Perón’s Tomb (Argentina): Small but fortified like a bunker, reflecting political obsession and public devotion.

- Forest Lawn Mausoleums (USA): Celebrity crypts with chandeliers, stained glass, and climate control. Eternity, now with amenities.

Modern tombs often trade scale for symbolism, but the message remains: remembrance is worth investing in.

What Extravagant Tombs Reveal About Us

These tombs aren’t really about death—they’re about anxiety. Fear of oblivion. Fear of insignificance. Fear that time will erase us like chalk in the rain.

Extravagant tombs attempt to negotiate with eternity. They say, Look at what I built. Surely that counts for something.

And perhaps it does.

Bottom Line

Extravagant tombs stand at the intersection of architecture, psychology, and philosophy. They are beautiful, excessive, and deeply human. Whether built from marble, limestone, or ego, they remind us that death does not silence ambition—it crystallises it.

In the end, these monuments don’t defeat mortality. They simply outlast it for a while. And maybe that’s enough.

FAQs

Because tombs were believed to ensure a successful afterlife, preserve status, and secure eternal remembrance—spiritual, social, and political insurance rolled into stone.

Yes, though modern extravagance is subtler, focusing on exclusivity, personalisation, and symbolism rather than sheer scale.

The Taj Mahal is widely considered the most expensive, with modern estimates placing its cost in the billions when adjusted for inflation.

Both. Religion provides the framework; ego often supplies the budget.

Because they humanise history. Tombs tell stories about love, fear, power, and the universal desire not to be forgotten.

Leave a Reply