How Colonialism Affected Burial Traditions and Cemetery Development

Cemeteries are never neutral spaces. They are cultural texts written in stone, soil, and silence. When colonial powers expanded across continents, they did not only impose political systems, languages, and borders—they also reshaped how societies buried their dead. And if you think burial practices are merely about disposal, think again. Funerary customs sit at the intersection of belief, power, land ownership, religion, and identity. Change how people bury their dead, and you quietly rewire how they understand life, ancestry, and memory.

Colonialism, in this sense, was not just an occupation of territory—it was an occupation of death. This article explores how colonialism affected burial traditions, reorganised cemetery spaces, enforced European funerary norms, and left behind landscapes of memory that are still contested today. Consider this a guided walk through a cemetery where every grave tells two stories: the one carved into stone, and the one erased beneath it.

Contents

- Burial Before Colonialism: Death as Continuity, Not Rupture

- Colonialism and the Moral Rebranding of Indigenous Death

- The European Cemetery Model: Order, Distance, and Control

- Segregated Death: Cemeteries as Racial Architecture

- Land, Law, and the Politics of Burial

- Hybrid Cemeteries: When Cultures Collide (and Compromise)

- Postcolonial Landscapes: Whose Dead Matter Now?

- Why Cemetery History Matters More Than We Think

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

Burial Before Colonialism: Death as Continuity, Not Rupture

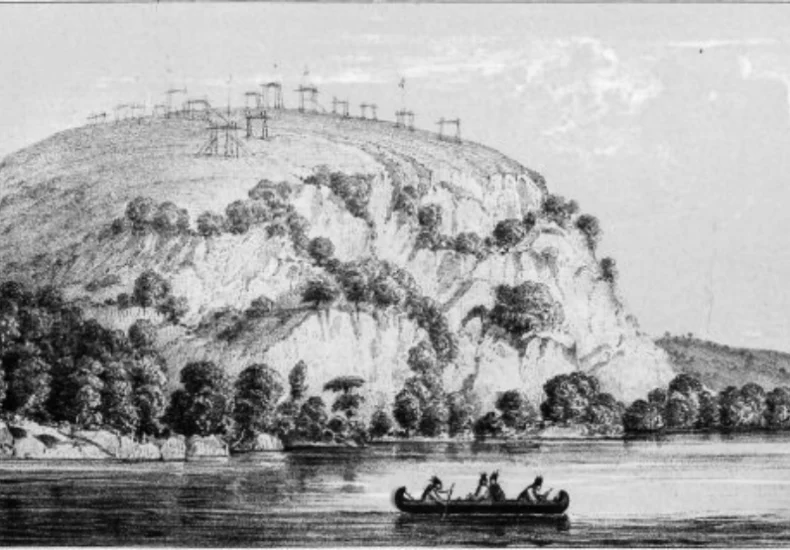

Before colonial intervention, burial practices across Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania were deeply embedded in cosmology and daily life. Death was rarely treated as a clean break. Instead, it was seen as a transformation—a shift from physical presence to ancestral influence.

Many societies buried their dead close to the home, within villages, or in sacred landscapes. Graves were not hidden away; they were woven into living space. Ancestors mattered. They advised, protected, punished, and remembered. Burial locations reinforced kinship ties, land claims, and spiritual continuity.

Colonial administrators, however, saw these practices as chaotic, unsanitary, and—perhaps most threatening—politically powerful. Burial grounds anchored people to land. And land, as colonial history repeatedly shows us, was never meant to remain in indigenous hands.

Colonialism and the Moral Rebranding of Indigenous Death

One of colonialism’s most effective tools was moral reframing. Indigenous burial customs were often labeled as “primitive,” “pagan,” or “uncivilised.” This language mattered. Once a practice was deemed immoral or irrational, it became easier to ban, relocate, or replace.

Christian missionaries played a major role here. Conversion was not limited to belief; it extended to the body, even after death. Baptism became a prerequisite for burial in consecrated ground. Indigenous funerary rites—songs, offerings, body positioning, grave goods—were discouraged or outright prohibited.

Death became regulated. Cemeteries became disciplinary spaces. The dead, like the living, were expected to conform.

The European Cemetery Model: Order, Distance, and Control

Colonial powers exported a very specific idea of what a cemetery should look like: planned, enclosed, regulated, and separate from daily life. This model emerged in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, driven by public health fears, urban overcrowding, and Enlightenment ideals of order.

Colonial cities adopted this model enthusiastically. New cemeteries were established on the outskirts of towns, often far from indigenous settlements. Burial within villages was banned. Graves were standardised. Registers were kept. Bodies were categorised.

This spatial separation was not accidental. Moving the dead away from the living weakened ancestral authority and loosened indigenous ties to land. It also reinforced colonial hierarchies—European cemeteries were landscaped, monumental, and permanent, while indigenous burial grounds were frequently neglected, relocated, or erased.

In stone and soil, inequality was made permanent.

The Lost Cemeteries of the World: Forgotten Burial Grounds Rediscovered

How Different Philosophies Influence Burial Practices

Segregated Death: Cemeteries as Racial Architecture

Colonial cemeteries were often explicitly segregated. Europeans, settlers, soldiers, and administrators were buried in carefully maintained sections—or entirely separate cemeteries—while indigenous populations were relegated to marginal spaces.

In British India, French North Africa, and settler colonies like South Africa and Australia, cemeteries mirrored the racial logic of colonial cities. Tomb size, material, inscriptions, and location reflected status and race. Marble for some, unmarked earth for others.

Even in death, colonial subjects were reminded of their place.

This segregation also shaped historical memory. European graves were documented, preserved, and commemorated. Indigenous graves, by contrast, were frequently unrecorded, leaving vast gaps in historical archives. Silence, here, was not accidental—it was structural.

Land, Law, and the Politics of Burial

Burial practices are inseparable from land rights. Colonial regimes understood this well. By regulating cemeteries, they could regulate claims to territory.

In many colonies, ancestral burial grounds were declared state property or reclassified as unused land. Graves were relocated to make way for plantations, railways, or urban expansion. The dead were displaced to facilitate the displacement of the living.

Legal systems backed this process. Colonial law often refused to recognise indigenous burial customs as legitimate land claims. What had once been sacred became, on paper, empty.

This legal erasure continues to haunt postcolonial societies, where disputes over land, heritage, and cemetery preservation remain unresolved.

Hybrid Cemeteries: When Cultures Collide (and Compromise)

Colonialism did not produce uniform outcomes. In many regions, burial practices evolved into hybrid forms, blending indigenous traditions with imposed European norms.

Graves might follow European layouts but include local symbols. Christian crosses might stand alongside ancestral offerings. Tomb inscriptions might appear in colonial languages, while rituals continued in indigenous ones.

These hybrid cemeteries are particularly fascinating. They reveal resistance disguised as adaptation. They show how colonised communities negotiated power not only in life, but in death.

Think of them as cultural palimpsests—layers of belief written over one another, never fully erased.

Lost & Found: How Ground-Penetrating Radar Helps Rediscover Forgotten Graves

Death & Digital Legacy: What Happens to Online Memorials

When Cemeteries Become Real Estate: The Business of Grave Reselling

Postcolonial Landscapes: Whose Dead Matter Now?

After independence, many former colonies inherited cemeteries shaped by colonial priorities. The question then became: what to do with them?

European cemeteries are often preserved as heritage sites, while indigenous burial grounds struggle for recognition. Colonial-era monuments still dominate urban landscapes, sparking debates about memory, injustice, and historical accountability.

In some cases, communities are reclaiming ancestral burial practices, restoring traditional rites, and challenging colonial definitions of legitimacy. In others, economic pressures and urban development continue to threaten historic cemeteries—especially those belonging to marginalised groups.

The dead, it seems, are still caught in political negotiations.

Why Cemetery History Matters More Than We Think

Studying colonial cemeteries is not about nostalgia or morbidity. It is about understanding how power operates through space, ritual, and memory.

Cemeteries teach us that colonialism did not end at the grave’s edge. It followed bodies underground, reorganised remembrance, and dictated who deserved permanence and who could be forgotten.

If history is written by the victors, cemeteries are where that writing becomes literal.

Bottom Line

Colonialism reshaped burial traditions not as a side effect, but as a deliberate strategy. By controlling how people buried their dead, colonial powers disrupted spiritual systems, weakened land claims, and enforced cultural hierarchies that persist to this day. Cemeteries became tools of governance—quiet, orderly, and deeply political.

Understanding this history allows us to read cemeteries differently. Every grave becomes a document. Every absence becomes evidence. And every reclaimed burial tradition becomes an act of resistance.

The dead, after all, still have much to say—if we know how to listen.

FAQs

Because burial practices are tied to land, belief systems, and social authority. Controlling death meant controlling memory, territory, and cultural continuity.

No. While many were suppressed, others survived in adapted or hybrid forms, often continuing quietly alongside imposed systems.

Through segregation, monument size, materials, location, and maintenance, cemeteries visually encoded colonial social structures.

Yes. Many are central to debates about heritage, land rights, historical injustice, and whose memory deserves preservation.

Because cemeteries reveal how power shapes culture beyond life—and understanding that helps us address ongoing inequalities rooted in colonial systems.

Archives

Calendar

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

Leave a Reply