The Rise of Garden Cemeteries: A Revolution in Burial Design

Cemeteries have not always been the serene, tree-lined parks we stroll through today. In fact, for centuries, the dead were crammed around churches in overcrowded graveyards where space was scarce, smells were abundant, and aesthetics were not exactly a priority. Then, in the early 19th century, a quiet revolution began—one that transformed burial grounds into landscaped sanctuaries. The garden cemetery movement was not just about where we bury our dead; it was about how we live with death.

But why did cemeteries suddenly become leafy havens rather than crowded churchyards? Let’s dig into (pun fully intended) the roots of this burial design revolution.

Contents

The Problem with Traditional Churchyards

Before the rise of garden cemeteries, most burials took place in churchyards. They were small, congested, and often unsanitary.

Picture narrow plots with barely legible headstones stacked haphazardly against each other, the ground uneven from centuries of burials. As urban populations exploded during the Industrial Revolution, the situation became unsustainable.

London, for instance, was infamous for its grim burial crisis. Decomposing bodies seeped into water supplies, epidemics spread, and the living could not escape the stench of death even in the shadow of the church. Something had to change—not just for aesthetics, but for public health.

The Birth of the Garden Cemetery Movement

Enter the 19th century: a period of grand ideas, urban reform, and the desire to civilise death itself. Inspired by Enlightenment ideals and Romanticism, reformers began to envision cemeteries not as grim necessities, but as cultural landscapes—places of reflection, beauty, and even recreation.

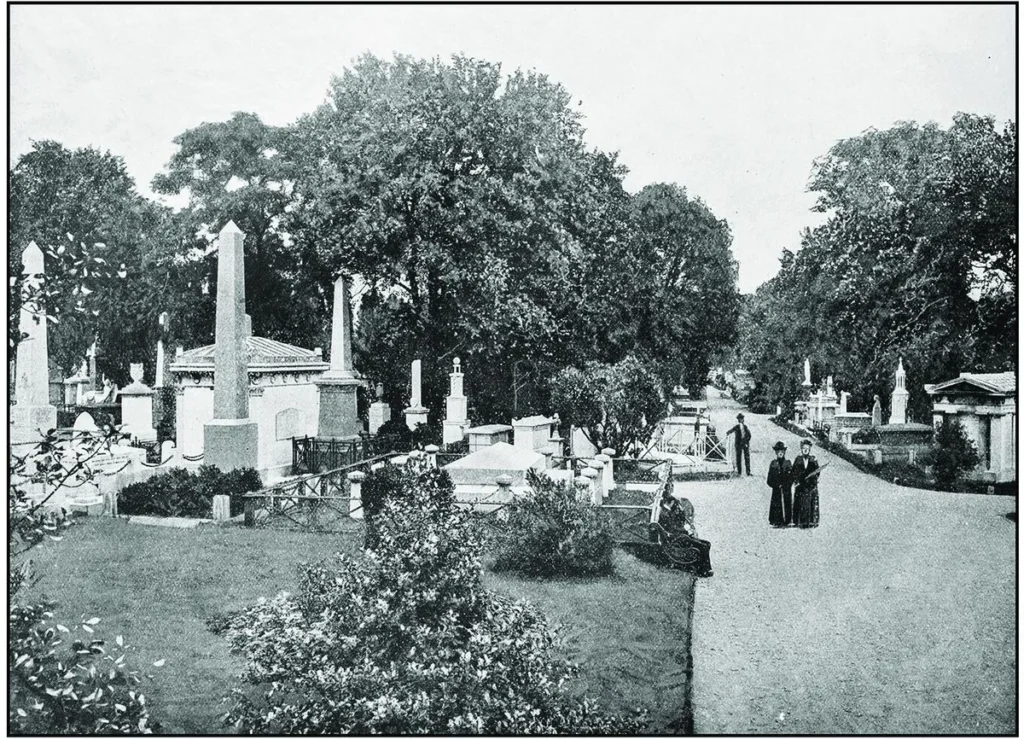

The first great example of this shift was Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris (1804). With its winding paths, leafy avenues, and monumental tombs, it became a sensation. No longer was the cemetery a gloomy backyard of the church—it was now a city of the dead, complete with neighbourhoods of graves and an air of dignity. People visited not only to mourn, but also to stroll, picnic, and be inspired by art and nature.

From Paris, the idea spread like wildfire. By the 1830s and 1840s, garden cemeteries were popping up across Europe and America: Mount Auburn in Boston (1831), Highgate in London (1839), and Glasnevin in Dublin (1832), among many others.

The Design Principles of Garden Cemeteries

What exactly made a cemetery “garden-like”? It wasn’t just about throwing in a few trees. Garden cemeteries followed a deliberate design philosophy:

- Landscaped Grounds: Rolling hills, carefully planted trees, and winding paths made cemeteries resemble public parks.

- Symbolic Planting: Evergreens represented eternal life, weeping willows conveyed mourning, and roses symbolised love.

- Monumental Art: Graves were adorned with sculptures, mausoleums, and elaborate headstones, reflecting both personal grief and societal values.

- Accessibility: These cemeteries were located outside crowded cities, offering fresh air and tranquility.

In essence, garden cemeteries were an urban planning solution as much as they were a burial reform. They became early prototypes for public green spaces at a time when city dwellers were starved of fresh air and beauty.

Cemeteries as Cultural Attractions

Here’s the twist: people didn’t just visit garden cemeteries to mourn their dead—they went for leisure. Families would stroll along the winding lanes, artists sketched mausoleums, and young lovers wandered beneath the shade of cypress trees. In fact, before public parks were commonplace, cemeteries were the parks.

Think of it this way: today we might pack a picnic for a Sunday afternoon in Central Park. In the 19th century, your great-great-grandparents might have done the same—but in Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Death and leisure coexisted in ways that would feel strange to us today, but it made perfect sense then. Cemeteries became places to commune with nature, art, and memory all at once.

The Social and Symbolic Impact

Garden cemeteries reshaped not just the urban landscape, but also the cultural relationship with death. They reflected:

- Romanticism: Death as a poetic return to nature.

- Class & Status: Elaborate tombs became a way for the wealthy to display influence beyond the grave.

- Democratisation of Memory: While the rich built monuments, ordinary citizens also found their final resting places dignified and beautiful.

- A Civic Function: Cemeteries provided educational value—visitors could learn history, symbolism, and even botany during their visits.

They were, in a way, open-air museums of grief, beauty, and memory.

Criticism and Controversies

Not everyone was charmed by the idea of garden cemeteries. Some critics argued they blurred the line between sacred ground and secular leisure.

Was it really appropriate to picnic among the dead? Others worried about commercialisation, as famous cemeteries began charging fees and selling plots like luxury real estate.

Moreover, by the late 19th century, even garden cemeteries began to face the same issues as churchyards: overcrowding, maintenance costs, and public debates about cremation versus burial. Yet despite these criticisms, their legacy endured.

Legacy of the Garden Cemetery Movement

Today, garden cemeteries remain some of the most visited and celebrated burial grounds in the world. Highgate Cemetery draws tourists for its Gothic allure and famous residents like Karl Marx. Père Lachaise receives millions of visitors annually, who come as much for Jim Morrison and Edith Piaf as for its architecture.

More importantly, the garden cemetery movement influenced the development of public parks and urban green spaces. Before New York had Central Park, Boston had Mount Auburn. The design principles of blending nature, art, and accessibility seeped into modern city planning. In short, the cemetery was the seed that grew into the public park.

Bottom Line

The rise of garden cemeteries was more than a burial reform—it was a cultural revolution. It transformed how societies treated the dead, how the living interacted with grief, and even how cities were designed.

By reimagining cemeteries as landscaped sanctuaries, the 19th century redefined death not as a grim necessity, but as an integral part of life’s cycle.

So next time you wander through a leafy cemetery, pause for a moment. The trees whisper history, the stones tell stories, and the paths remind us that even in death, design matters.

After all, in the garden cemetery, mortality was not hidden away—it was made beautiful.

FAQs

They transformed burial grounds from overcrowded churchyards into landscaped parks, improving public health while reshaping cultural attitudes toward death.

Père Lachaise in Paris (1804) is widely considered the first true garden cemetery, inspiring similar sites worldwide.

At the time, cemeteries doubled as green spaces before public parks existed. They offered fresh air, scenic walks, and an educational glimpse into art and history.

They pioneered the integration of green spaces into urban planning, serving as models for the creation of public parks.

Yes. They continue to function as historical landmarks, tourist attractions, and peaceful places of reflection, blending heritage, art, and nature.

I always learn something from your articles.