Memento Mori: The Dark Beauty of Death Imagery in Cemeteries

Death, though inevitable, has always been one of humanity’s greatest obsessions. We write about it, fear it, laugh at it nervously, and above all, attempt to immortalise it in stone. Cemeteries, those silent libraries of lives once lived, are far more than final resting places—they are outdoor galleries of art, philosophy, and symbolism. Among their most striking features lies a recurring theme: memento mori, Latin for “remember you must die.” This concept has fascinated scholars, artists, and curious wanderers alike for centuries.

But why, you might ask, would anyone want constant reminders of death carved into tombstones? Isn’t life grim enough? The answer lies in the paradoxical beauty of death imagery. It is not just about gloom and doom but about wisdom, humility, and even a peculiar kind of hope. Let’s take a walk through the stone-carved metaphors, winged skeletons, and eternal hourglasses that populate graveyards, and uncover why memento mori continues to captivate us.

Content

- The Origins of Memento Mori: A Whisper from Antiquity

- The Cemetery as a Canvas for Death’s Symbols

- The Gothic Obsession: Beauty in the Macabre

- Philosophy Carved in Stone: Lessons from the Dead

- Memento Mori and Modern Culture: Still Alive in Death

- Why Cemeteries Still Fascinate Us

- Bottom Line

- Remember, you must die—so live well.

- FAQs

The Origins of Memento Mori: A Whisper from Antiquity

The idea of remembering death is as old as civilisation itself. Ancient Romans had a chilling but practical practice: during triumphal parades, a servant would whisper to victorious generals, “Memento mori.”

In other words, “Don’t get cocky—death comes for you, too.” It was a grounding reminder that glory, power, and wealth all crumble into dust.

Christianity later absorbed the concept, weaving it into medieval and Renaissance art. Skeletons danced in frescoes, skulls appeared in devotional paintings, and entire architectural motifs revolved around mortality.

Cemeteries became the stage where this philosophy took physical form, carved into stone by stonemasons who knew that every chisel strike was, quite literally, a meditation on death.

The Cemetery as a Canvas for Death’s Symbols

When you step into an old cemetery, you’re not just walking among graves—you’re entering a vast encyclopedia of symbols. Some are obvious (a skull is hard to misinterpret), while others are subtler, requiring a trained eye.

- Skulls and Crossbones: Not just for pirate flags, these stark emblems once dominated Puritan and colonial graveyards. They served as blunt warnings: “Death is near, prepare yourself.”

- Hourglasses with Wings: Time flies—literally. This imagery reminds us that every grain of sand slipping away brings us closer to the inevitable.

- Grim Reapers and Scythes: If the hourglass doesn’t get the message across, the skeletal reaper with his harvest tool surely will. He’s there to remind us that death spares no one.

- Broken Columns: These represent a life cut short, often marking the grave of someone who died young.

- Sleeping Figures: Less terrifying but equally symbolic, they suggest that death is merely an eternal slumber.

What’s remarkable is that these symbols weren’t meant to terrify. Quite the opposite: they offered comfort by framing death as natural, predictable, and universal.

The Gothic Obsession: Beauty in the Macabre

Fast-forward to the 18th and 19th centuries, when cemeteries underwent a stylistic transformation. The grim, almost cartoonish skeletons of earlier graveyards gave way to more romantic, even sentimental, imagery. Angels, weeping willows, and sorrowful maidens draped across tombs became the new norm.

Why the shift? The Gothic movement swept through Europe and America, reshaping art, architecture, and literature. Death was no longer a blunt statement; it was something to be romanticised, even aestheticised. Cemeteries like Highgate in London or Père Lachaise in Paris became pilgrimage sites not just for mourning but for marveling at the artistry of tombs.

In this era, memento mori didn’t vanish—it simply changed clothes. The skull and bones became cherubs and roses, but the message remained: remember your mortality, and live meaningfully.

Philosophy Carved in Stone: Lessons from the Dead

So, what does all this morbid art teach us? If you strip away the ornate carvings and baroque details, the message is shockingly practical.

Memento mori is less about death itself and more about life. It is a reminder not to squander time on trivialities, because the hourglass is always running. In today’s productivity-driven world, this idea might sound like motivational content disguised as Gothic poetry.

Think about it: doesn’t the skull on a gravestone whisper the same wisdom as a self-help guru? “Use your time wisely, because you won’t get another.”

Moreover, death imagery democratises human existence. Kings, peasants, artists, and merchants all lie beneath the same ground, united by the same skeletal fate. Cemeteries, in this sense, are the most equal places on Earth.

Oil on canvas, between 1654 and 1672. Photo by Van-Ham

Memento Mori and Modern Culture: Still Alive in Death

You may think skulls and skeletons belong to the dusty past, but memento mori is alive and well in modern culture. From Day of the Dead sugar skulls in Mexico to the popularity of Gothic fashion and tattoos, the fascination with death’s imagery persists.

Even minimalist headstones of today sometimes carry subtle nods to the old tradition—tiny hourglasses, carved roses, or poetic epitaphs that hint at life’s brevity.

In fact, the digital world has resurrected memento mori in surprising ways. Apps track how many weeks of your life you have left, encouraging you to “seize the day.” Instagram aesthetics romanticise abandoned cemeteries with moody filters.

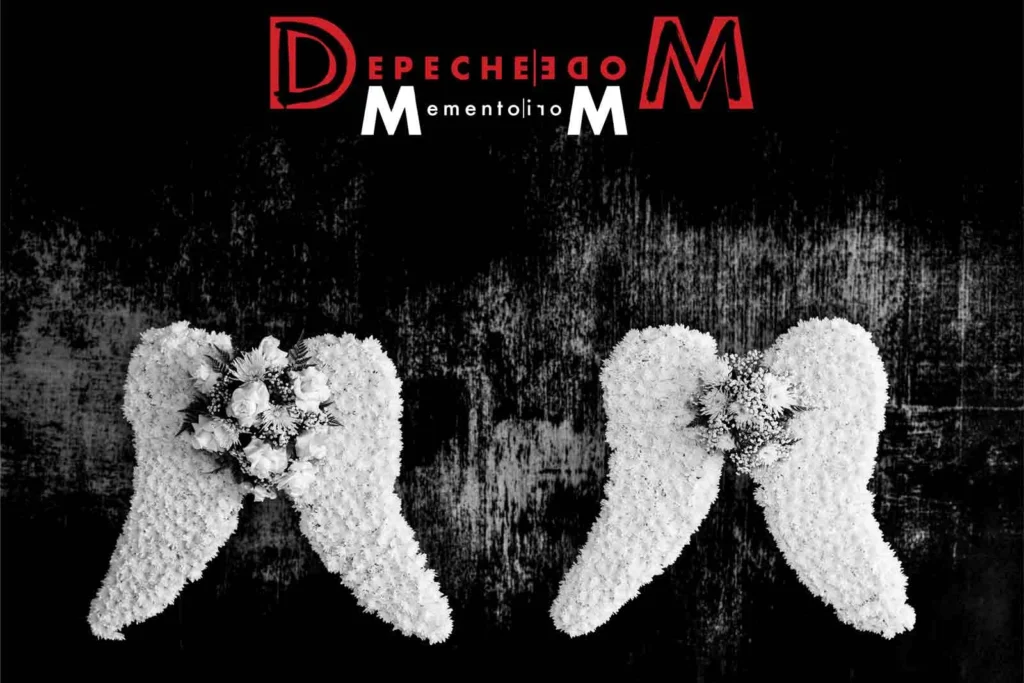

And let’s not forget pop culture: skull motifs dominate everything from heavy metal album covers to luxury fashion houses like Alexander McQueen. Death, it seems, never goes out of style.

Why Cemeteries Still Fascinate Us

Why are we still drawn to cemeteries, even if we’re not mourning someone there? Part of it is curiosity, but part of it is the unique cocktail of fear and beauty they offer.

Cemeteries are places where the physical, spiritual, and philosophical collide. They allow us to confront mortality without having to face our own demise directly.

Think of cemeteries as classrooms of stone, where the syllabus is simple but profound: You will die. Everyone does. So what are you doing with your life in the meantime? That’s the power of memento mori—it grabs you by the shoulders, shakes you a little, and says, “Make it count.”

Bottom Line

At first glance, memento mori may seem like a grim philosophy, one that revels in decay and despair. But in truth, it is the opposite. It is a philosophy of urgency, clarity, and even gratitude.

The skull on a gravestone is not a threat but a teacher. The winged hourglass is not a terror but a nudge: time is precious, don’t waste it.

Cemeteries, with their intricate carvings and haunting imagery, are not morbid playgrounds for the curious but archives of human wisdom. They whisper, they warn, and they remind us of the one certainty we all share.

By embracing the dark beauty of death imagery, we learn to live—not in fear, but with awareness, intention, and perhaps even joy.

So next time you wander through a graveyard and find yourself staring into the hollow sockets of a carved skull, don’t recoil. Listen.

It’s speaking to you across the centuries, with the simplest of messages:

Remember, you must die—so live well.

FAQs

It means “remember you must die.” The phrase, often symbolised by skulls, hourglasses, or skeletons, reminds visitors of life’s fragility and the importance of living meaningfully.

Skulls were popular in colonial and Puritan cemeteries because they offered a blunt visual reminder of mortality, encouraging the living to prepare for the afterlife.

Early cemeteries favored grim, stark symbols like skeletons and skulls. By the 19th century, Gothic and Romantic influences brought softer imagery such as angels, flowers, and draped urns.

Absolutely. Modern culture embraces it through tattoos, fashion, and even apps designed to remind us of life’s brevity. The philosophy has simply adapted to new mediums.

Yes. While it acknowledges death, its true purpose is to encourage living fully. Far from being morbid, it’s an invitation to appreciate time and live with intention.

Leave a Reply