Plague Pits & Mass Graves: How Epidemics Shaped Burial Practices

When we think of cemeteries, the images that usually come to mind are carefully laid out rows of headstones, sculpted angels, or perhaps a romanticized mausoleum or two. What we don’t immediately imagine are pits—vast, hurriedly dug trenches where the dead were laid side by side, often nameless and forgotten. Yet, plague pits and mass graves tell us as much about human history as any ornate graveyard. They are the dark underbelly of our relationship with mortality—grim reminders of how societies coped when death arrived not in whispers, but in thunderclaps.

In this article, we’ll journey through centuries of epidemics, pandemics, and crises to uncover how disease shaped burial practices. Ready to dig in? (Pun fully intended.)

Contents

- The Birth of the Plague Pit: When Death Outran Ritual

- From Individual Burials to Collective Memory

- Epidemics as Architects of Urban Cemeteries

- The Science Beneath the Soil

- Ritual, Religion, and the Fear of Contagion

- Mass Graves Beyond the Plague

- Symbolism of the Pit: Memory, Shame, or Resilience?

- Lessons for Today

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

The Birth of the Plague Pit: When Death Outran Ritual

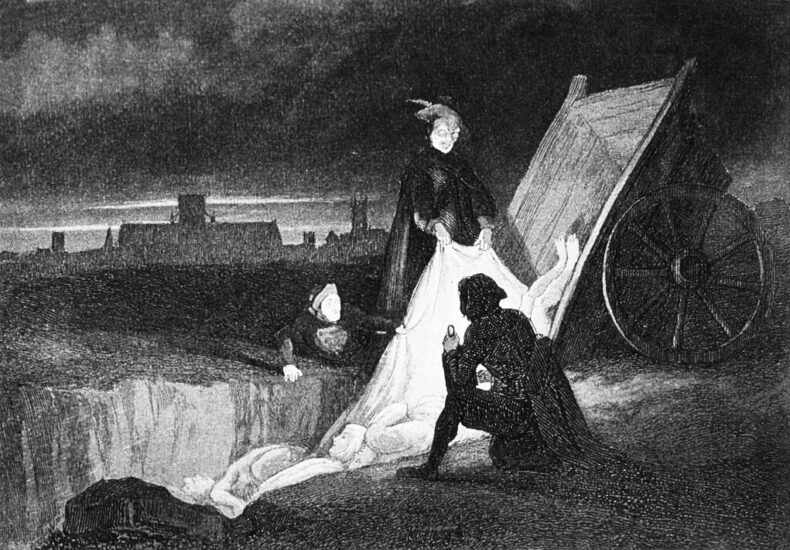

Imagine a city like London in the 14th century. Narrow streets, overflowing cesspits, and the dreaded sound of carts wheeling through neighbourhoods as the cry of “Bring out your dead!” echoed in the air. During the Black Death (1347–1351), death became so frequent and overwhelming that the traditional parish graveyard could no longer contain it.

Enter the plague pit: massive communal graves dug outside city walls to accommodate thousands of bodies. These weren’t designed with reverence in mind but with necessity—fast disposal to prevent contagion (or so people believed). Rituals were stripped bare, funerals abandoned, and anonymity became the rule rather than the exception.

Was it disrespectful? Perhaps. But it was also a survival mechanism. Epidemics demanded speed, not ceremony.

From Individual Burials to Collective Memory

Human beings have an intrinsic desire to honour the dead. Yet during epidemics, practicality often trumped tradition. In plague pits, coffins were rare; bodies were layered, sometimes with quicklime to hasten decomposition. What’s fascinating is how collective burial became a temporary cultural norm, rewriting centuries of individualised mourning practices.

Anthropologists see these shifts not as lapses in humanity but as adaptations. Societies adjusted rituals in response to crisis, and these adjustments became part of collective memory. Think of it as a cultural scar—visible reminders of a wound that healed but left its mark.

Epidemics as Architects of Urban Cemeteries

Here’s the paradox: mass graves ultimately shaped the future of dignified burial. The shock of plague pits exposed the inadequacies of parish graveyards, particularly in Europe. By the 18th and 19th centuries, urban planners and public health officials pushed for the creation of garden cemeteries—spacious, landscaped burial grounds designed both for sanitary purposes and civic beauty.

Without plague pits & mass graves as cautionary tales, would we have cemeteries like Père Lachaise in Paris or Highgate in London? Epidemics forced societies to rethink burial not just as a religious duty, but as an urban planning issue, merging health, hygiene, and aesthetics.

The Science Beneath the Soil

Plague pits & mass graves are more than historical curiosities—they’re also scientific treasure troves. Archaeologists have excavated sites across London, Florence, and beyond, unearthing remains that tell us not only about death, but also about life.

By studying teeth and bones from plague victims, scientists have reconstructed the DNA of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium behind the Black Death. These findings shed light on how the plague spread, mutated, and even how some survivors developed genetic resistance. In a way, plague pits were the first accidental laboratories—frozen time capsules that let us peek into the microscopic wars of the past.

Ritual, Religion, and the Fear of Contagion

Mass graves didn’t just disrupt burial practices—they rattled theological assumptions. In Christian Europe, the body was believed to require proper burial for resurrection at the Last Judgement. Tossing corpses into pits en masse raised existential fears: would these souls be denied eternal rest?

Clergy scrambled to reassure the faithful, offering blanket absolutions or mass prayers. But the fear lingered, creating a tension between faith and pragmatism. Epidemics essentially forced religion to adapt, softening rigid rituals in favour of compassionate flexibility. The theology of death had to keep pace with the biology of disease.

Mass Graves Beyond the Plague

Though the Black Death looms largest, epidemics throughout history—from cholera in the 19th century to the influenza pandemic of 1918—resurrected the need for collective burial. Even today, mass graves remain a chilling reality in times of crisis.

During the early months of COVID-19, aerial images of freshly dug trenches in places like Hart Island, New York, reminded us that the plague pit is not just a medieval artifact. It’s a recurring pattern whenever mortality outpaces infrastructure.

Symbolism of the Pit: Memory, Shame, or Resilience?

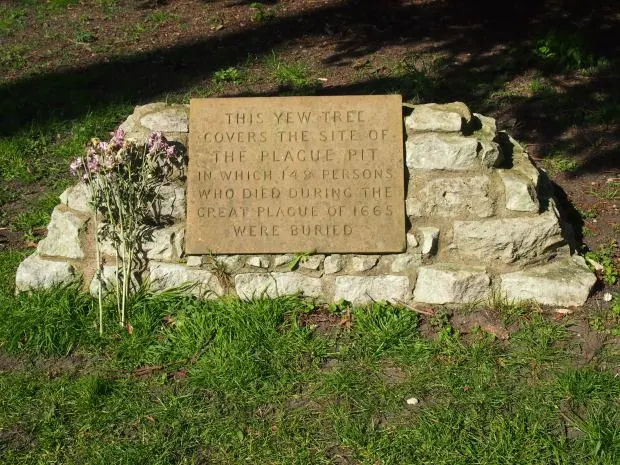

How societies remember mass graves varies. Some plague pits are marked and memorialised, serving as sobering sites of collective grief. Others are paved over, forgotten, or unearthed centuries later during construction projects—an awkward reminder beneath modern feet.

The symbolism of mass graves is dual: they represent both shame (the inability to care for the dead individually) and resilience (the communal act of survival). In this paradox lies their power. A plague pit is both an end and a beginning, a scar and a seed.

Lessons for Today

Why should we care about plague pits now? Because epidemics, unfortunately, are not relics of the past. As climate change, urbanisation, and globalisation increase the risk of pandemics, history’s burial lessons remind us of two truths:

- Crisis reshapes culture faster than comfort does.

- Our response to death reflects our values as much as our science.

Plague pits tell us that while disease disrupts rituals, it also inspires innovation—from public health reforms to the very cemeteries we stroll in today.

Bottom Line

Plague pits and mass graves are not merely holes in the ground; they are profound historical texts written in soil and bone. They show us how humans wrestle with mortality when ritual collapses under the weight of necessity. They reveal the adaptability of culture, the vulnerability of faith, and the resilience of communities in crisis.

So next time you wander through a peaceful cemetery, take a moment to remember: behind the manicured lawns and sculpted angels lies a history dug in haste, born from epidemic terror, and etched forever in our collective memory.

Grave matters, indeed.

FAQs

A plague pit is a large communal grave, often dug during epidemics when traditional burial grounds could no longer handle the number of deaths.

No. Mass graves appeared globally during epidemics, from medieval Europe to colonial India and even modern crises.

Yes. In Christian Europe, improper burial raised fears about eternal rest, though clergy adapted rituals to ease anxieties.

No. Pathogens like Yersinia pestis cannot survive in buried remains for centuries. Excavated plague pits are safe for study.

They exposed the shortcomings of parish graveyards, inspiring the rise of larger, landscaped cemeteries designed for both hygiene and aesthetics.

Leave a Reply