Victorian Mourning Culture: Why Death Became an Art Form

Death, as the Victorians saw it, was not the end but a grand performance — a ritualised dance between grief and aesthetics. While today we often avoid talking about death (let alone decorating with it), the Victorians embraced it with an almost theatrical intensity. From black crêpe dresses to hair jewellery, mourning photography to elaborate funerals, their obsession with death was not morbid—it was meaningful. But why did mourning become such an elaborate art form in the 19th century? Let’s wander, candle in hand, through the cobwebbed corridors of Victorian mourning culture to find out.

Contents

- The Queen Who Set the Tone for a Nation in Mourning

- Dressing for Death: Fashioning Grief in Black and Lace

- Funerals Fit for the Living and the Dead

- The Paradox of Death in an Age of Progress

- Memento Mori: Remember You Must Die (Beautifully)

- Gender and Grief: The Feminisation of Mourning

- Graveyards as Galleries: Where Sculpture Met Symbolism

- The Business of Bereavement: When Grief Became Profitable

- The Death of Mourning: How the 20th Century Moved On

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

The Queen Who Set the Tone for a Nation in Mourning

It all began, as many Victorian trends did, with Queen Victoria herself. When Prince Albert died in 1861, the queen plunged into a state of grief so deep it reshaped an entire nation’s relationship with death. Her black attire, worn for the rest of her life, became a symbol of eternal devotion. If the monarch mourned so extravagantly, society followed suit.

In true Victorian fashion, grief became not just an emotion—it became etiquette. There were rules for how to mourn, what to wear, how long to grieve, and even how to decorate your home. Mourning became performative, structured, and—let’s be honest—a little competitive. The longer and more visibly you mourned, the more respectable you were.

Dressing for Death: Fashioning Grief in Black and Lace

If modern fashion tells the world who we are, Victorian mourning attire told the world who we had lost. The “mourning wardrobe” was a sophisticated system of fabrics and colours that communicated your grief’s intensity and stage.

The strictest period, deep mourning, demanded full black — matte bombazine, crepe, or paramatta cloth that absorbed light and reflected sorrow. Jewellery was minimal, save for one haunting exception: hair jewellery. Locks of hair from the deceased were intricately woven into brooches, rings, and lockets, turning memory into wearable art.

After deep mourning came half mourning, a transitional phase that allowed muted purples, grays, and lavenders—a slow return to life through colour. Mourning wasn’t just emotional—it was seasonal, fashionable, and deeply symbolic.

Funerals Fit for the Living and the Dead

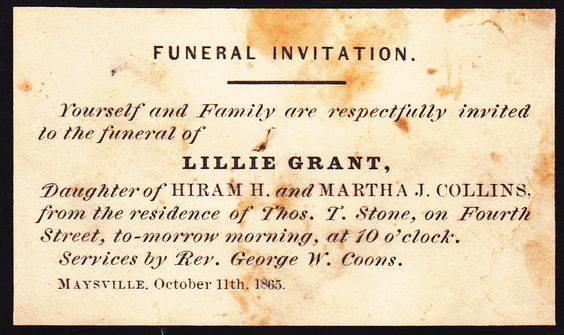

In the Victorian era, funerals were grand productions, complete with horse-drawn hearses, plumed feathers, mourning carriages, and processions that snaked through town like rivers of black silk.

Death had become democratised—thanks to the Industrial Revolution, even the lower classes could now afford respectable burials through the rise of burial clubs and undertakers. The funeral industry was born, and with it, the commercialisation of death. You could now buy grief, or at least, rent it.

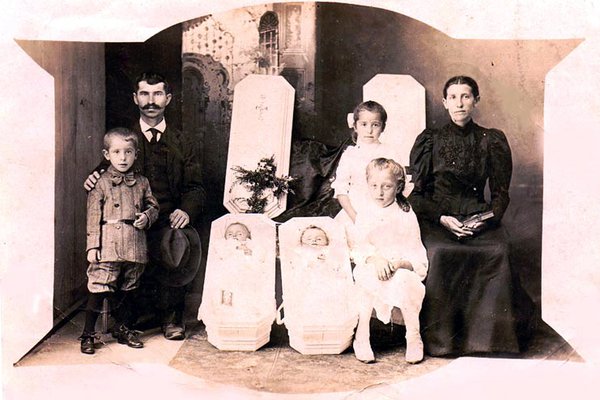

Professional mourners were hired to cry at funerals, and mourning stationery was embossed in black borders to announce one’s sorrow in style. Even mourning photography—a practice that strikes us as macabre today—was seen as a tender gesture. Families posed with their deceased loved ones, capturing the stillness of eternity in a single photograph.

The Paradox of Death in an Age of Progress

Here lies the great paradox of Victorian culture: the same era that produced scientific breakthroughs, industrial expansion, and modern medicine was utterly captivated by death.

Why? Because progress was terrifying. The Industrial Revolution transformed everything—cities swelled, disease spread, and faith faltered. In an age of uncertainty, the Victorians turned to ritual to find meaning. Mourning culture became an art form precisely because it offered structure in a chaotic world.

By aestheticising death, Victorians made it bearable. They found beauty in sorrow, order in chaos, and even creativity in grief. Death became a canvas—painted in black velvet and pearls.

Memento Mori: Remember You Must Die (Beautifully)

The phrase memento mori—Latin for “remember you must die”—was the heartbeat of Victorian art and design. It appeared in paintings, poetry, jewellery, and architecture, reminding the living of their mortality.

Post-mortem portraits and mourning art turned the deceased into muses. Painters depicted angelic children asleep in eternal peace. Photographers softened the edges of reality with ethereal lighting. Death was not denied; it was domesticated—a familiar guest at the parlour table.

Even cemeteries reflected this artistic sensibility. The newly built garden cemeteries—such as the Père Lachaise in Paris—inspired a new kind of beauty in death. These spaces were not just for mourning; they were public parks, sculpture gardens, and moral theaters where art, nature, and eternity met.

Gender and Grief: The Feminisation of Mourning

Mourning was, quite literally, women’s work. While men returned to public life within months, women were expected to perform grief for years. Entire industries catered to their mourning attire, accessories, and etiquette.

The widow became a powerful cultural figure—a symbol of devotion and virtue, but also an object of sympathy and sometimes suspicion. Queen Victoria, the eternal widow, was both revered and pitied.

Through mourning, women found a strange kind of agency. Within the rigid decorum of black silk and lace, they wielded emotional authority. Their grief was public, visible, and codified—a language that only women seemed to truly speak.

Graveyards as Galleries: Where Sculpture Met Symbolism

To stroll through a Victorian cemetery is to walk through an open-air art gallery of sorrow. Angels, urns, broken columns, clasped hands, and veiled faces adorn the tombstones, each symbol whispering a coded message about faith, love, and mortality.

The Victorians viewed cemeteries not as places of decay but as gardens of memory. Architecture and nature intertwined: ivy-covered mausoleums, marble cherubs, and pathways that led the living through curated landscapes of grief.

Every stone was a story. Every monument, a performance. Death, after all, deserved its own aesthetic.

The Business of Bereavement: When Grief Became Profitable

Victorian mourning culture wasn’t just emotional—it was economic. The death industry blossomed. Milliners, jewellers, photographers, and printers all cashed in on grief. Mourning goods were advertised in newspapers with the same enthusiasm as tea sets and corsets.

Funeral directors, previously simple coffin-makers, reinvented themselves as “undertakers” offering full-service experiences. A proper funeral was not just a farewell; it was a social statement.

In a world obsessed with status and propriety, even the dead had reputations to maintain.

The Death of Mourning: How the 20th Century Moved On

By the early 20th century, the Great War changed everything. With millions dead, mourning lost its ornamentation. Black veils and hair jewellery felt suddenly inadequate—and even distasteful. The collective grief of a generation rendered personal ritual obsolete.

The modern era sought simplicity over spectacle, efficiency over emotion. Mourning became private, understated, and—ironically—less human. In rejecting the excesses of Victorian death culture, society also lost something profound: the art of mourning beautifully.

Bottom Line

Victorian mourning culture may seem extravagant, even morbid, by today’s standards. But beneath the lace and crêpe lies a timeless truth: the Victorians understood that grief needs expression. By turning death into art, they gave sorrow a shape, a ritual, a beauty.

In a world that prefers to hide death behind hospital doors and polite euphemisms, perhaps we could learn something from them. Mourning, after all, is not a weakness—it’s a language of love carved in marble and stitched in black silk.

FAQs

Black symbolised humility, loss, and spiritual reflection. It was a visual cue of grief and respect for the deceased.

It often included jet, black enamel, or woven human hair—especially from the deceased—used to create sentimental keepsakes.

It varied by relationship: widows mourned up to two years, while other relatives followed shorter, prescribed durations.

Post-mortem photography was a way to preserve memory in an age before casual portraits were common—especially for children.

The Victorians remind us that expressing grief openly can be healing, and that death, when acknowledged artistically, can deepen our appreciation of life.

Leave a Reply