Celtic Crosses & Ancient Symbols: Tracing the Origins of Cemetery Motifs

Cemeteries are, in many ways, open-air libraries—places where stories are carved in stone rather than printed on paper. And among those carved narratives, the Celtic cross and other ancient symbols stand out like illuminated manuscripts in a dusty archive. They invite us closer, whispering of older beliefs, lost rituals, and the stubborn human need to declare meaning even in the face of mortality. But where exactly do these motifs come from? Why do they persist? And what do they reveal about the people who carved them?

In this article, we’ll walk through centuries of symbolism—from pagan spirals to Christian iconography—trace the evolution of the iconic Celtic cross, and examine how ancient motifs made their way into modern graveyards. Ready to read stones the way archaeologists read ruins? Let’s begin.

Contents

- The Allure of Ancient Cemetery Motifs

- Pre-Christian Roots: Spirals, Sun Wheels, and Knotwork

- Early Christianity Arrives: Symbolic Fusion, Not Replacement

- The Birth of the Celtic Cross

- The Victorian Revival: How Celtic Symbols Entered Modern Cemeteries

- Not Just Crosses: Other Ancient Cemetery Motifs with Celtic Roots

- Interpreting Cemetery Motifs Today

- Bottom Line

- FAQs

The Allure of Ancient Cemetery Motifs

Walk through any historic cemetery in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, or even parts of the United States, and you’ll find symbols that feel older than the graves they mark.

Spirals, knots, sun wheels—motifs that look suspiciously like they belong in a Neolithic temple rather than a Victorian burial ground. And in many ways, they do.

Symbolism in cemeteries works much like a palimpsest: layers of meaning written over older layers but never fully erasing them. The cross you see today may have started as a sun symbol. That pretty knotwork pattern? Once a metaphysical diagram. Gravestones, in essence, are cultural time capsules pretending to be décor.

Why the persistence? Simple: humans crave continuity. We want our dead to rest within the embrace of symbols older and bigger than we are.

Pre-Christian Roots: Spirals, Sun Wheels, and Knotwork

Before Celtic crosses became the cemetery’s unofficial fashion statement, ancient cultures across the British Isles decorated stone with symbols tied to nature, cosmology, and spirituality.

Spirals: The Eternal Loop of Life

The spiral is among the oldest symbols in Celtic art, appearing in Neolithic sites such as Newgrange (ca. 3200 BCE). It represented cycles—life, death, rebirth—and the movement of the sun across the sky. Essentially, it was a cosmic GIF long before the internet.

When spirals appear on gravestones, they quietly suggest continuity rather than finality. They are the ancient world’s way of telling us, “Relax, death is a doorway. Not a dead end.”

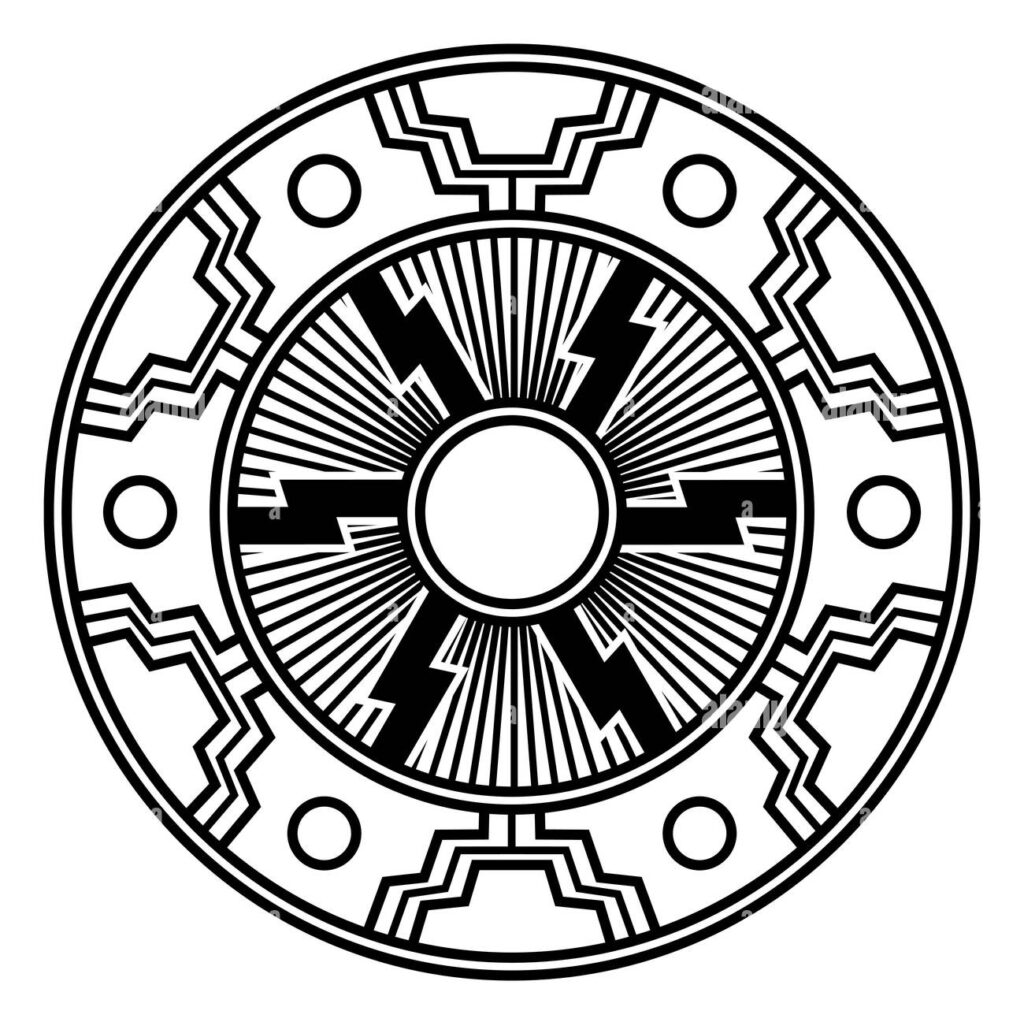

Sun Wheels: Proto-Crosses

Long before Christianity arrived, the sun wheel—circle with spokes—symbolised solar power, cosmic order, and divine protection. In some regions, the wheel morphed into cross-shaped variations, making it surprisingly easy for early missionaries to adapt it into Christian symbolism.

If you’ve ever thought, “That Celtic cross looks like a cross wearing a halo,” you’re not wrong. The haloed cross is a direct descendant of the solar wheel, a synergy of pagan geometry and Christian theology.

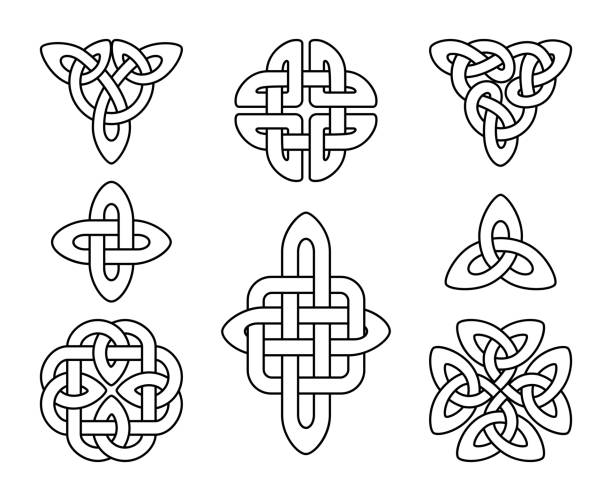

Knotwork: Interlacing the Seen and Unseen

Celtic knotwork appears in stone carvings, manuscripts, pottery, weaponry—you name it. But unlike spirals, knots have no beginning or end. They map the intangible: interconnectedness, infinity, the weaving of worlds.

On gravestones, knots declare a belief that life is bound to something greater. Think of them as the ancient equivalent of saying, “Gone, but connected forever.”

Early Christianity Arrives: Symbolic Fusion, Not Replacement

When Christianity reached the Celtic world (5th–7th century CE), it didn’t bulldoze the existing symbolic culture. Instead, it borrowed, blended, adapted. Missionaries demonstrated a remarkable skill for cultural compromise—a kind of spiritual UX design.

Celtic art evolved into what scholars now call Insular art, defined by its fusion of Christian imagery with pagan patterns. Manuscripts like the Book of Kells are glowing examples of this syncretism: gospel stories woven in knotwork, crosses ornamented with spirals and zoomorphic creatures.

Cemeteries quickly adopted this artistic hybrid. A grave marker was not just a marker—it became a canvas for theology, myth, and ethnic identity. And nothing captured this fusion better than the emerging Celtic cross.

The Birth of the Celtic Cross

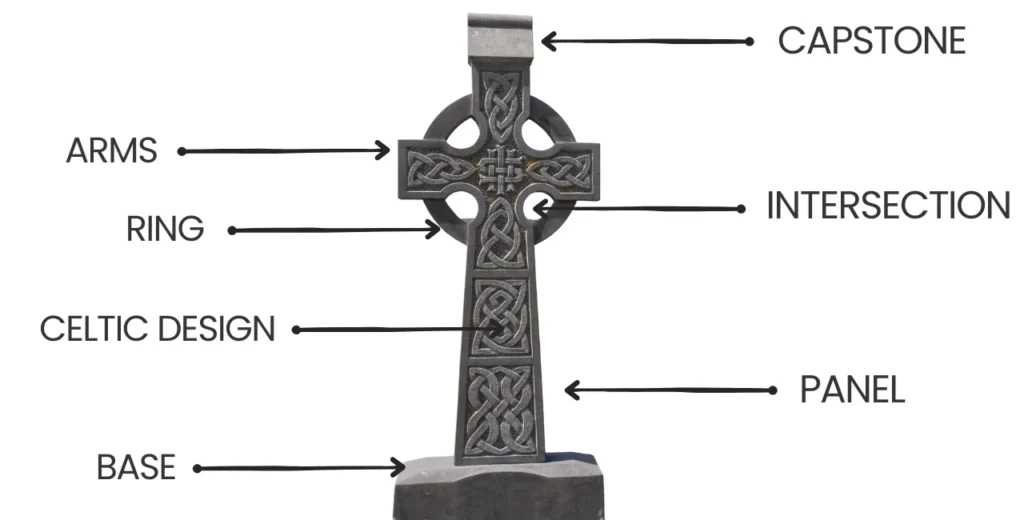

What Makes a Celtic Cross ‘Celtic’?

A Celtic cross is instantly recognisable: a Latin cross with a distinctive ring encircling the intersection. That ring—sometimes thick and structural, other times delicate and decorative—is the feature that sets it apart from other Christian crosses.

Origins: Myth or History?

Theories abound, though scholars generally agree on two possibilities:

- Structural Support Theory

The ring originally reinforced tall stone crosses, preventing the arms from snapping off. Practical, sturdy, very medieval. - Solar Symbolism Theory

The ring echoes the ancient sun wheel, symbolising divine light radiating across the world. Artistic, spiritual, very Celtic.

The truth is likely a combination—engineering meets theology.

High Crosses: The Showpieces of Medieval Ireland

By the 8th–12th centuries, Celtic crosses reached their artistic peak. Monumental carved “high crosses” dotted monastic landscapes, functioning as outdoor scripture for largely illiterate populations.

They featured:

- Biblical scenes carved like comic panels

- Interlace patterns symbolising eternity

- Sunburst motifs merging pagan echoes with Christian narrative

These were not mere grave markers—they were sermons in stone.

The Victorian Revival: How Celtic Symbols Entered Modern Cemeteries

If you’ve ever wandered through a 19th-century cemetery and thought, “Why does this feel like a Celtic art museum?”, you’re experiencing the Victorian Celtic Revival.

Why the Revival Happened

Victorians adored symbolism, nostalgia, and romantic nationalism. They resuscitated medieval arts like stained glass, Gothic architecture, and, of course, Celtic ornamentation.

Two forces fueled this revival:

- The rise of archaeology

Excavations inspired an obsession with ancient British and Irish culture. - Romantic literature

Writers like Sir Walter Scott popularised Celtic landscapes, legends, and aesthetics.

Victorian stonemasons adopted Celtic motifs for gravestones because families increasingly wanted markers that felt “timeless,” symbolic, spiritual—yet also fashionable. The Celtic cross fit the brief perfectly.

The Ideology Behind the Style

The Victorian era linked Celtic symbols with:

- A noble, mystical past

- Moral integrity and Christian virtue

- Ethnic identity (especially in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales)

Hence, Celtic crosses became ideal monuments for:

- Clergymen

- Veterans

- Children

- Nationalists

- Individuals of Irish or Scottish descent

The symbolism offered comfort and cultural pride, turning cemeteries into landscapes of heritage.

Not Just Crosses: Other Ancient Cemetery Motifs with Celtic Roots

Cemeteries filled with Celtic imagery rarely stop at the cross. Look closely and you’ll discover an entire symbolic vocabulary hiding in plain sight.

Triskeles

A triple spiral or three-legged form symbolising motion, energy, and tripartite cosmology (life-death-rebirth, earth-sea-sky, maiden-mother-crone).

On gravestones, it often signals protection and perpetual movement.

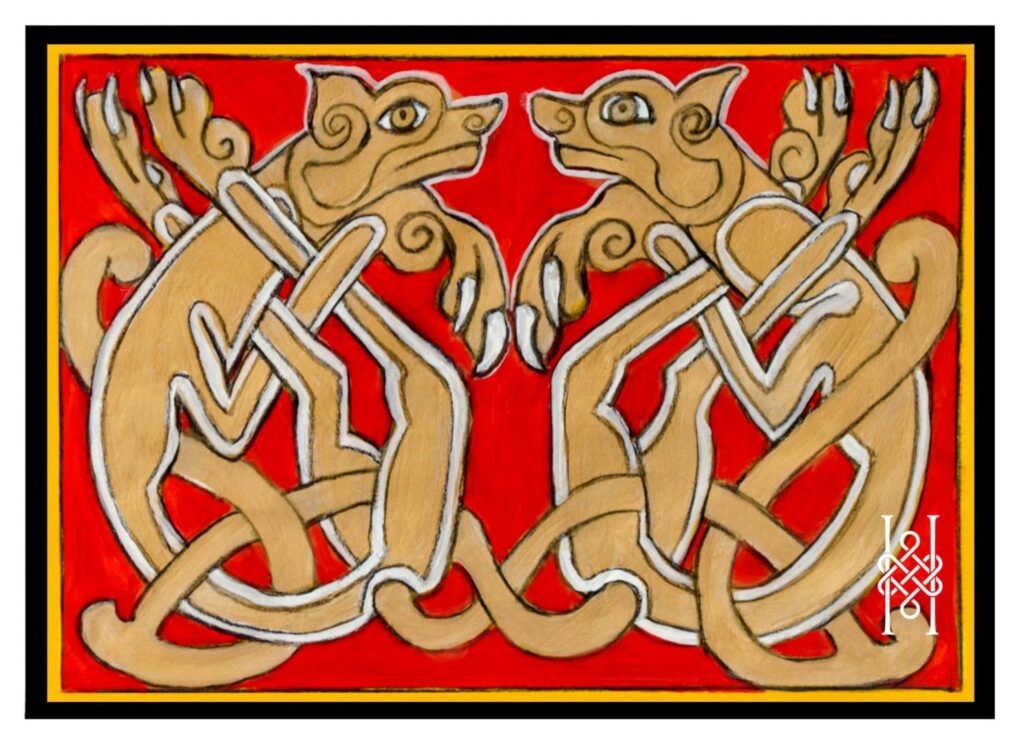

Zoomorphic Designs

Animals—including serpents, birds, and hounds—appear interlaced within knotwork. They held spiritual significance:

- Serpents: renewal

- Birds: the soul in flight

- Hounds: loyalty, guardianship

These images turned grave markers into symbolic bestiaries.

The Claddagh

Though later in origin (17th century), the heart-hands-crown motif is widespread in modern cemeteries, symbolising love, friendship, and loyalty.

Ogham Script

This early medieval writing system sometimes appears on markers intended to evoke ancestry, heritage, or mysticism. It’s decorative, yes—but also an explicit nod to Ireland’s earliest literate culture.

Interpreting Cemetery Motifs Today

Why do these symbols still resonate in the 21st century? Because cemeteries are not merely places for mourning—they are places for meaning-making.

Aesthetic Appeal

Celtic motifs are timeless and visually captivating. The knotwork alone feels like an algorithm of artistry—mathematically precise yet spiritually expressive.

Cultural Identity

For people with Irish, Scottish, or Welsh ancestry, these motifs connect them to their roots.

Spiritual Versatility

A Celtic cross can be devoutly Christian, quietly pagan, or comfortably both. This symbolic ambiguity makes it accessible.

Narrative Depth

Every motif is a story. Every carving is a memory. In a way, ancient symbols transform cemeteries into museums of belief systems.

The Modern Celtic Cross: Between Heritage and Trend

Today, Celtic crosses appear globally—from Irish diaspora cemeteries in America to modern memorial parks in Australia. They continue evolving:

- Laser-cut granite versions mimic ancient carved patterns

- Eco-burial markers incorporate Celtic symbolism in biodegradable materials

- Artistic reinterpretations merge Celtic geometry with contemporary design

Even in today’s minimalist design era, Celtic symbols persist because they meet humanity’s persistent need for metaphors of eternity.

Bottom Line

The Celtic cross may be the poster child of ancient cemetery motifs, but it is only one chapter in a much longer symbolic saga. Spirals, knots, sun wheels, animals, and scripts whisper stories of continuity, identity, spirituality, and cultural memory. They remind us that cemeteries are far from silent—they speak in the language of symbols, carved across centuries.

We trace these motifs not only to understand the past but to understand ourselves: our fears, our hopes, our need to belong to something timeless.

After all, what is a gravestone if not a final attempt at storytelling?

FAQs

The ring likely developed from a blend of practical and symbolic reasons: structural support for stone crosses and an adaptation of earlier sun-wheel motifs.

Not necessarily. Many motifs have pre-Christian origins, representing cycles, protection, continuity, or identity rather than specific doctrine.

Although ancient in origin, they surged in popularity during the 19th-century Celtic Revival, becoming a staple of Victorian cemetery art.

The spiral is among the earliest, appearing in Neolithic art thousands of years before the Celtic cross existed.

Some are, especially in heritage cemeteries, while others reinterpret the style using modern materials and techniques. The symbolism, however, remains largely intact.

Leave a Reply